Chapter 5: Bottom-Up Parsing

5.1 Overview

A bottom-up parser uses a parsing stack, which contain both tokens and nonterminals, and also some extra state info. It is empty at the beginning, and contains the start symbol at the end.

A bottom-up parser is also called a shift-reduce parser, because it has two possible actions besides accept:

- Shift a terminal from the front of the input to the front of the stack.

- Reduce a string α at the top of stack to a nonterminal A, given the BNF choice \(A \rightarrow \alpha\).

Note that in order to use bottom-up parsing, the grammar has to be augmented with a new start symbol. i.e. if \(S\) is the start symbol, a new production \(S' \rightarrow S\) is added.

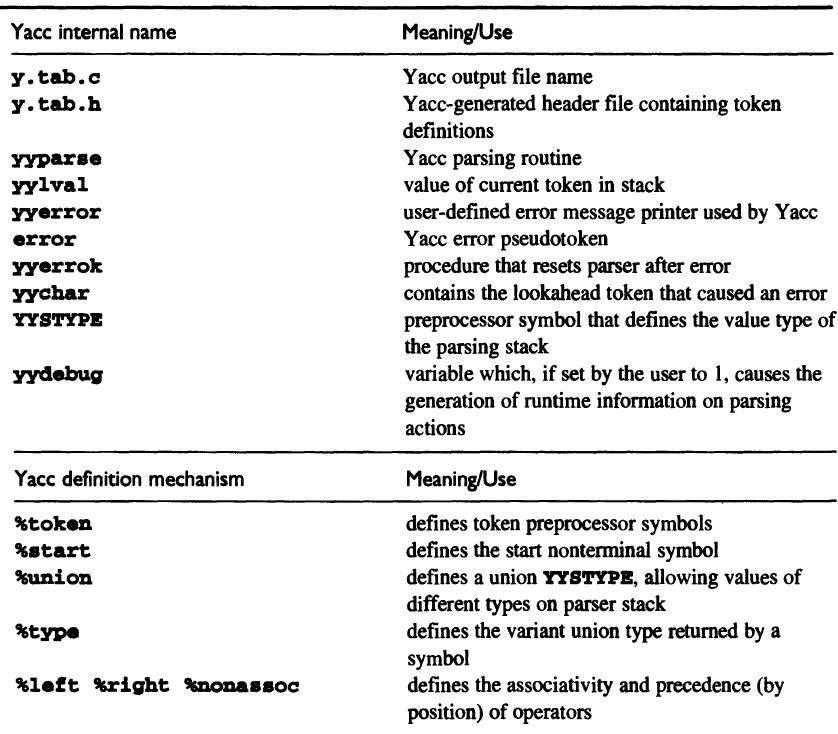

For example, the parsing actions for

\[\begin{align} &E' \rightarrow E\\ &E \rightarrow E + \mathbf{n} | \mathbf{n} \end{align}\]

Problems:

- We sometimes need to look deeper in the parsing stack (stack lookahead) to determine the next step.

- The next token in the input may also need to be taken into consideration.

Right sentential form:

- Each of the intermediate strings of terminals and nonterminals in the corresponding derivation of a shift-reduce parser is called a right sentential form. For example, the derivation represented in the parsing actions above is \(E' \Rightarrow E \Rightarrow E + \mathbf{n} \Rightarrow \mathbf{n} + \mathbf{n}\). Each string is a right sentential form.

- Each sentential form is split in the parsing stack and the input. The sequence symbol in the parsing stack of a right sentential form is called a viable prefix of the right sentential form. For example, \(E\), \(E+\) and \(E + \mathbf{n}\) are viable prefixes of \(E + \mathbf{n}\). \(\mathbf{n} +\) is not a viable prefix of \(\mathbf{n} + \mathbf{n}\).

- Handle: A shift-reduce parser will shift terminals from the input to the stack until it is possible to perform a reduction to obtain the next right sentential form. This will occur when the string of symbols on the top of the stack matches the right-hand side of the production that is used in the next reduction. This string, together with the position in the right sentential form where it occurs, and the production used to reduce it, is called the handle of the right sentential form. e.g. \(\mathbf{n}\) and the production \(E \rightarrow \mathbf{n}\) is the handle for the right sentential form \(\mathbf{n} + \mathbf{n}\).

5.2 Finite Automata of LR(0) Items and LR(0) Parsing

5.2.1 LR(0) Items

An LR(0) item (or just item for short) of a context-free grammar is a production choice with a distinguished position in its right-hand side. We indicate this distinguished position by a period.

e.g. Consider the grammar

\[\begin{align} & S' \rightarrow S \\& S \rightarrow \text{ ( } S \text{ ) } S | \epsilon \end{align}\]The grammar has the following eight items:

\[\begin{align} & S' \rightarrow .S \\& S' \rightarrow S. \\& S \rightarrow .\text{ ( } S \text{ ) } S \\& S \rightarrow \text{ ( } .S \text{ ) } S \\& S \rightarrow \text{ ( } S .\text{ ) } S \\& S \rightarrow \text{ ( } S \text{ ) } .S \\& S \rightarrow \text{ ( } S \text{ ) } S. \\& S \rightarrow . \end{align}\]An item records an intermediate step in the recognition of the right-hand side of a particular grammar rule choice.

-

The item \(A \rightarrow \beta . \gamma\) constructed from the grammar rule choice \(A \rightarrow \beta \gamma\) means that \(\beta\) has already been seen and that it may be possible to derive the next input token from \(\gamma\). This means \(\beta\) must appear at the top of the stack.

- Initial items: An item such as \(A \rightarrow .\alpha\) that means we may be about to recognize an \(A\) by using the grammar rule choice \(A \rightarrow \alpha\).

- Complete items: An item such as \(A \rightarrow \alpha.\) that means \(\alpha\) now resides on the top of the parsing stack and may be the handle, if \(A \rightarrow \alpha\) is to be used for the next reduction.

5.2.2 Finite Automata of Items

NFA

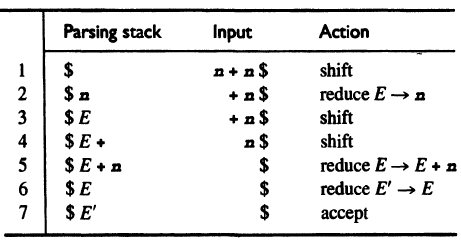

Consider the item \(A \rightarrow \alpha . X \eta\) where \(X\) is a token or a nonterminal. Then we have the transition

-

If X is a token, this transition corresponds to a shift of X from the input to the top of the stack during the parse.

-

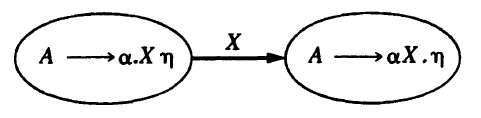

If X is a nonterminal, the interpretation of this transition is more complicated. However, this definitely means that X is pushed onto the stack, and this can only occur during a reduction by a production \(X \rightarrow \beta\), which is preceded by the state \(X\rightarrow.\beta\). Therefore, for every item \(A\rightarrow\alpha.X\eta\) we must add the ε-transition for every production choice \(X\rightarrow\beta\):

Initial state: any initial item \(S\rightarrow.\alpha\) could serve as a start state, but that’s too many. That’s why we augment the grammar by a single production \(S'\rightarrow S\), and \(S'\) becomes the start state of the augmented grammar, and \(S'\rightarrow.S\) becomes the start state of the NFA.

Accepting states: No accepting states. The parser itself will decided when to accept.

NFA to DFA

Use subset construction.

5.2.3 The LR(0) Parsing Algorithm

Let s be the current state. The actions of the algorithm are defined as follows:

- If state s contains any item of the form \(A\rightarrow \alpha . X \beta\), where \(X\) is a terminal, then shift the current input token onto the stack. If this token is \(X\), and state s contains \(A\rightarrow \alpha . X \beta\), then push the new state containing the item \(A\rightarrow \alpha X.\beta\) to the stack. Otherwise, raise an error.

- If state s contains any complete item of the form \(A\rightarrow \gamma.\), then reduce by the rule \(A\rightarrow \gamma\).

- If the rule is \(S'\rightarrow S\), and the input is empty, accept the input. If the input is not empty, raise an error.

- Otherwise, the following actions should be done:

- Remove \(\gamma\) and its corresponding states from the stack.

- Go back in the DFA to the state from which the construction of \(\gamma\) began, which has the form of \(B\rightarrow \alpha.A\beta\).

- Push \(A\) onto the stack, and push the new state containing the item \(B\rightarrow\alpha A.\beta\).

A grammar is set to be an LR(0) grammar if the above roles are unambiguous. A grammar is LR(0) if and only if each state is a shift state (containing only “shift” items) or a reduce state (containing a single complete item).

The DFA can be combined into a parsing table.

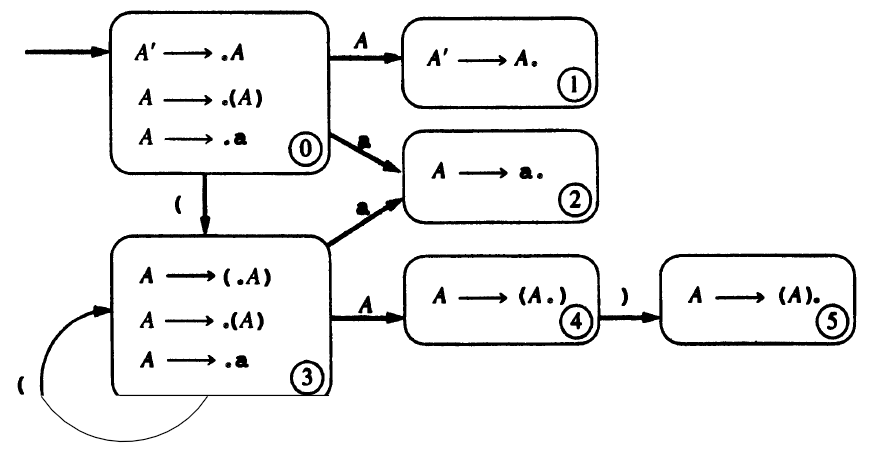

e.g. The DFA:

The parsing table:

5.3 SLR(1) Parsing

5.3.1 The SLR(1) Parsing Algorithm

Let s be the current state. The actions are defined as follows:

- If state s contains any item of the form \(A\rightarrow \alpha . X \beta\), where \(X\) is a terminal, and \(X\) is the next token of the input string, then shift the current input token onto the stack, and push the new state containing the item \(A\rightarrow \alpha X.\beta\).

- If state s contains any complete item of the form \(A\rightarrow \gamma.\), and the next token in the input string is in Follow(A), then reduce by the rule \(A\rightarrow \gamma\).

- If the rule is \(S'\rightarrow S\), accept the input. (This will happen only if the next input token is $$.)

- Otherwise, the following actions should be done:

- Remove \(\gamma\) and its corresponding states from the stack.

- Go back in the DFA to the state from which the construction of \(\gamma\) began, which has the form of \(B\rightarrow \alpha.A\beta\).

- Push \(A\) onto the stack, and push the new state containing the item \(B\rightarrow\alpha A.\beta\).

- If the next input token is such that neither of the above applies, raise an error.

A grammar is set to be an SLR(1) grammar if the rule above has no ambiguity, i.e. if and only if for any state s, the following conditions are satisfied:

- For any item \(A\rightarrow\alpha.X \beta\) in s with \(X\) a terminal, there is no complete item \(B\rightarrow\gamma.\) in s with \(X\) in \(\text{Follow}(B)\). (Violation constitutes a shift-reduce conflict)

- For any two complete items \(A\rightarrow\alpha.\) and \(B\rightarrow\beta.\) in s, \(\text{Follow}(A)\) and \(\text{Follow}(B)\) is empty. (Violation constitutes a reduce-reduce conflict)

The difference between this and the LR(0) algorithm is that the decisions on which grammar rule to use is delayed until the last possible moment.

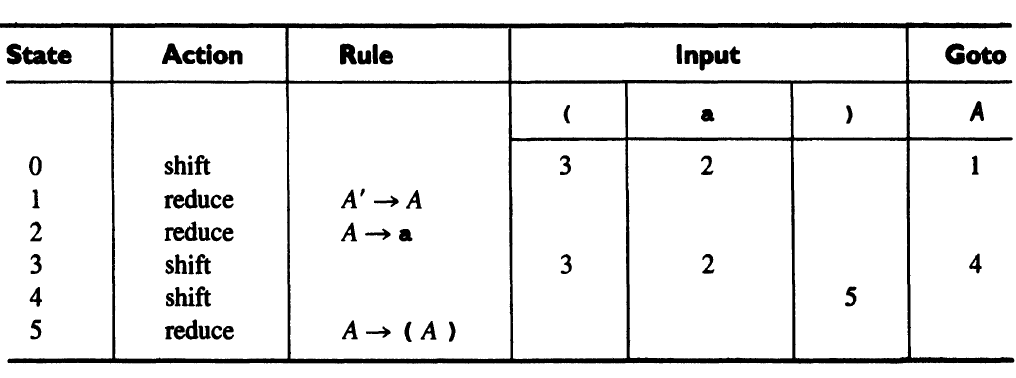

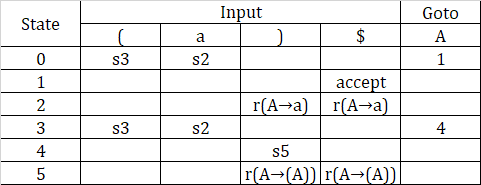

The construction of the SLR(1) parsing table is a bit different from that of the LR(0). The most significant difference is that a state can be a shift and reduce state at the same time The parsing table for the aforementioned DFA is:

(s for shift, r for reduce)

5.3.2 Disambiguating Rules for Parsing Conflicts

- Shift-reduce conflicts: prefer the shift over the reduce. This automatically applies the most closely nested rule for the dangling else problem.

- Reduce-reduce conflicts: more difficult. Probably indicates an error in grammar design.

5.3.3 Limits of SLR(1) Parsing Power

SLR(1) is powerful enough to handle almost all practical language structure. However, there are some limits.

5.3.4 SLR(k) Grammars

Use \(\text{First}_k\) and \(\text{Follow}_k\) sets.

5.4 General LR(1) and LALR(1) Parsing

5.4.1 Finite Automata of LR(1) Items

SLR(1) constructs the DFA that ignores lookaheads, then applies the lookaheads. LR(1) uses a new DFA that has the lookaheads built into it. An LR(1) items looks as:

\[[A\rightarrow \alpha.\beta, a]\]Where \(A\rightarrow\alpha.\beta\) is an LR(0) item and \(a\) is the lookahead.

Definition of LR(1) transitions:

- Given an LR(1) item \([A\rightarrow\alpha.X \gamma, a]\), where \(X\) is a terminal or nonterminal, there is a transition on \(X\) to the item \([A\rightarrow \alpha X. \gamma, a]\).

- Given an LR(1) item \([A\rightarrow \alpha.B \gamma, a]\), where \(B\) is a nonterminal, there are ε-transitions to items \([B\rightarrow .\beta, b]\) for every production \(B\rightarrow \beta\) and for every token \(b\) in \(\text{First}(\gamma a)\).

The rule 2 keeps track of the context in which the structure \(B\) needs to be recognized.

The start state for an LR(1) DFA is \([S'\rightarrow .S, \\)]$$.

5.4.2 The LR(1) Parsing Algorithm

The is generally the same as the SLR(1) algorithm, except that it uses the lookahead tokens in the LR(1) terms instead of the Follow sets.

Let s be the current state. The actions are defined as follows:

- If state s contains any item of the form \([A \rightarrow \alpha . X \beta, a]\), where \(X\) is a terminal, and \(X\) is the next input token, then shift the current input token onto the stack, and push the new state that contains the item \([A\rightarrow \alpha X . \beta, a]\).

- If state s contains the complete item \([A \rightarrow \alpha ., a]\), and the next input token is \(a\), then reduce by the rule \(A \rightarrow \alpha\).

- If the rule is \(S' \rightarrow S\), accept the input string.

- Otherwise, do the following:

- Remove the string \(\alpha\) and all its corresponding states from the stack.

- Go back in the DFA to the state from which the construction of \(\alpha\) began which contains an item of the form \([B \rightarrow \alpha . A \beta, b]\).

- Push \(A\) onto the stack, and push the state containing the item \([B \rightarrow \alpha . A \beta, b]\).

- If the next input token is such that neither of the above applies, raise an error.

A grammar is set to be an LR(1) grammar if the rule above has no ambiguity, i.e. if and only if for any state s, the following conditions are satisfied:

- For any item \([A\rightarrow\alpha.X \beta, a]\) in s with \(X\) a terminal, there is no item in s of the form \([B\rightarrow\gamma., X]\) .Violation constitutes a shift-reduce conflict)

- There are no two items in s of the form \([A\rightarrow \alpha., a]\) and \([B\rightarrow \beta., a]\) (Violation constitutes a reduce-reduce conflict)

The parsing table of the LR(1) grammar has the same form of that of a SLR(1) grammar.

5.4.3 LALR(1) Parsing

The size of an LL(1) DFA is large due to the many different states that have the same set of the first components in their items (the LL(0) items), while differing only in their second components (the lookaheads). The LALR(1) algorithm combines the states that share the same first components. Each combined state has a set of lookaheads, which is often smaller than the corresponding Follow sets, thus retains some of the benefit of LR(1) parsing. Formally:

- The core of a state of the DFA of LR(1) items is the set of LR(0) items consisting of the first components of all LR(1) items in the state.

- FIRST PRINCIPLE: The core of a state of the DFA of LR(1) items is a state of the DFA of LR(0) items.

- SECOND PRINCIPLE: Given two states \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) of the DFA of LR(1) items that have the same core, if there is a transition of the symbol \(X\) from \(s_1\) a state \(t_1\), then there is also a transition on \(X\) from state \(s_2\) to a state \(t_2\), and the states \(t_1\) and \(t_2\) have the same core.

The algorithm for LALR(1) parsing is identical to the general LR(1) parsing algorithm.

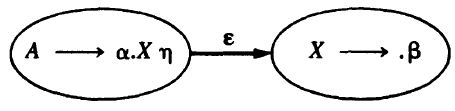

5.5 Yacc: An LALR(1) Parser Generator

5.5.1 Yacc Basics

Format of a Yacc spec file:

// tokens, data types, grammar rules,

// and C code that goes into the beginning of output file

{definitions}

// grammar rules in BNF form,

// with C code to be executed when a rule is recognized

%%

{rules}

%%

// optional

{auxiliary routines}

An example Yacc spec file:

// exp -> exp addop term | term

// addop -> + | -

// term -> term mulop factor | factor

// multop -> *

// factor -> ( exp ) | NUMBER

// definitions

// code to be inserted at the beginning of output

%{

#include <stdio.h>

#include <ctype.h>

%}

// declaration of tokens

// single-chracter tokens can be included directly

// in the grammar rules surrounded by single quotes

%token NUMBER

// tokens are assigned a numeric value. We can override

// the default by specifying it explicitly, e.g.

// %token NUMBER 18

%%

// grammar rules

// the first one is the start symbol, unless specified by

// %start command

// $$n are pseudovariables that represents the nth token on the

// right-hand side. $$ represents the token on the left-hand side.

command : exp { printf("%d\n", $$1); }

; // allow printing of the result

exp : exp '+' term { $$ = $$1 + $$3; }

| exp '-' term { $$ = $$1 - $$3; }

| term { $$ = $$1; }

;

term : term '*' factor { $$ = $$1 * $$3; }

| factor { $$ = $$1; }

;

factor : NUMBER { $$ = $$1; }

| '(' exp ')' { $$ = $$2; }

;

%%

int main() {

// The parsing procedure. Returns 0 on success,

// 1 on failure

return yyparse();

}

// The scanning procedure.

// Return the next input, unless its a digit, in which case

// it recognizes the single multicharacter token NUMBER and

// return its value in the variable yylval.

int yylex(void) {

int c;

while ((c = getchar()) == ' ') {

continue;

}

if (isdigit(c)) {

ungetc(c, stdin);

scanf("%d", &yylval);

return NUMBER;

}

if (c == '\n') {

return 0;

}

return c;

}

int yyerror(char* s) {

fprintf(stderr, "%s\n", s);

return 0;

}

5.5.2 Yacc Options

-d: Output a header file.

-v: Generate a textual description of the LALR(1) parsing table.

5.5.3 Parsing Conflicts and Disambiguating Rules

-

Shift-reduce conflicts: Yacc prefers shift.

-

Reduce-reduce conflicts: Yacc prefers the rule listed first.

-

Yacc has several ad hoc mechanisms for specifying operator precedence and associativity separately from a grammar that is otherwise ambiguous. For example, we can write:

%left '+' '-' %left '*'to indicate that +, - and * are left associative, and * has higher precedence.

(We have

%rightto specify right associativity, and%nonassocto specify that the repeated operators are not allowed at the same level.)

5.5.4 Debugging a Yacc Parser

In the spec file, insert

#define YYDEBUG 1

at the beginning to output debug info.

5.5.5 Arbitrary Value Types in Yacc

The values of an expression in Yacc are integers by default. To change it, we should redefine the data type by the symbol YYSTYPE, e.g.

#define YYSTYPE double

inside the brackets %{ ... %} in the definition section.

Sometimes different tokens have different types. We can declare them using %union:

%union { double val;

char op; }

Then use %type to define the type of each nonterminal:

%type <val> exp term factor

%type <op> addop mulop

We can also define a new data type in a separate include file and define YYSTYPE to be this type.

5.5.6 Embedded Actions in Yacc

Yacc interprets an embedded action

A : B {/* action */} C;

as being equivalent to

A : B E C;

E : {/* action */}; // E is an ε-production

Summary